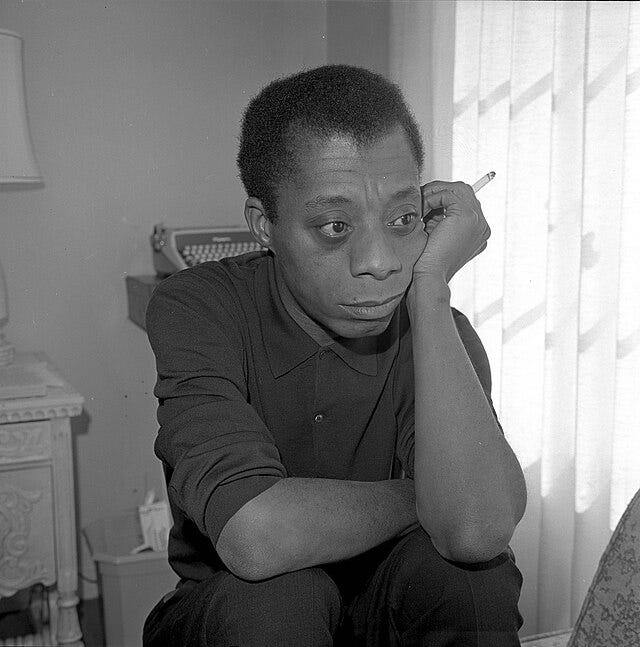

I'm excited to start a new series this week highlighting some of my favorite writers. I want to start with James Baldwin, an author who consistently astounds me with his talent. He’s the type of writer who crafts sentences so good that I reread them over and over, and then end up staring at the wall trying to process what I just read.

In this love letter to Baldwin’s work, I’ll briefly look at some of his books, share words I love, and list resources for diving deeper. Whether you adore Baldwin, haven't read him yet, or fall somewhere in between, I hope you get a sense of why his work matters and what you might be able to gain from it.

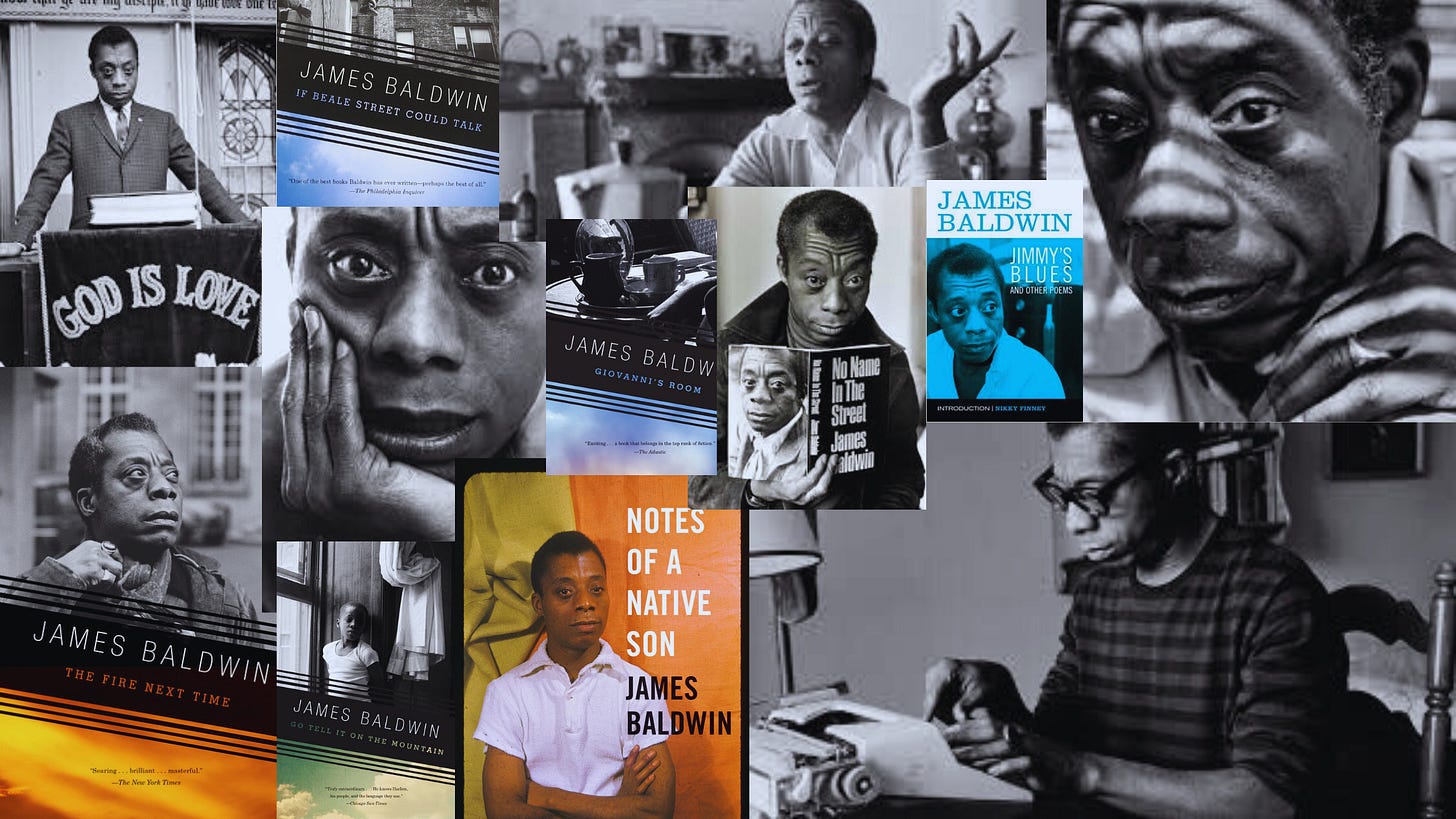

Author Spotlight: James Arthur Baldwin

Born: August 2, 1924 in New York, New York

Died: December 1, 1987 in Saint Paul de Vence, France

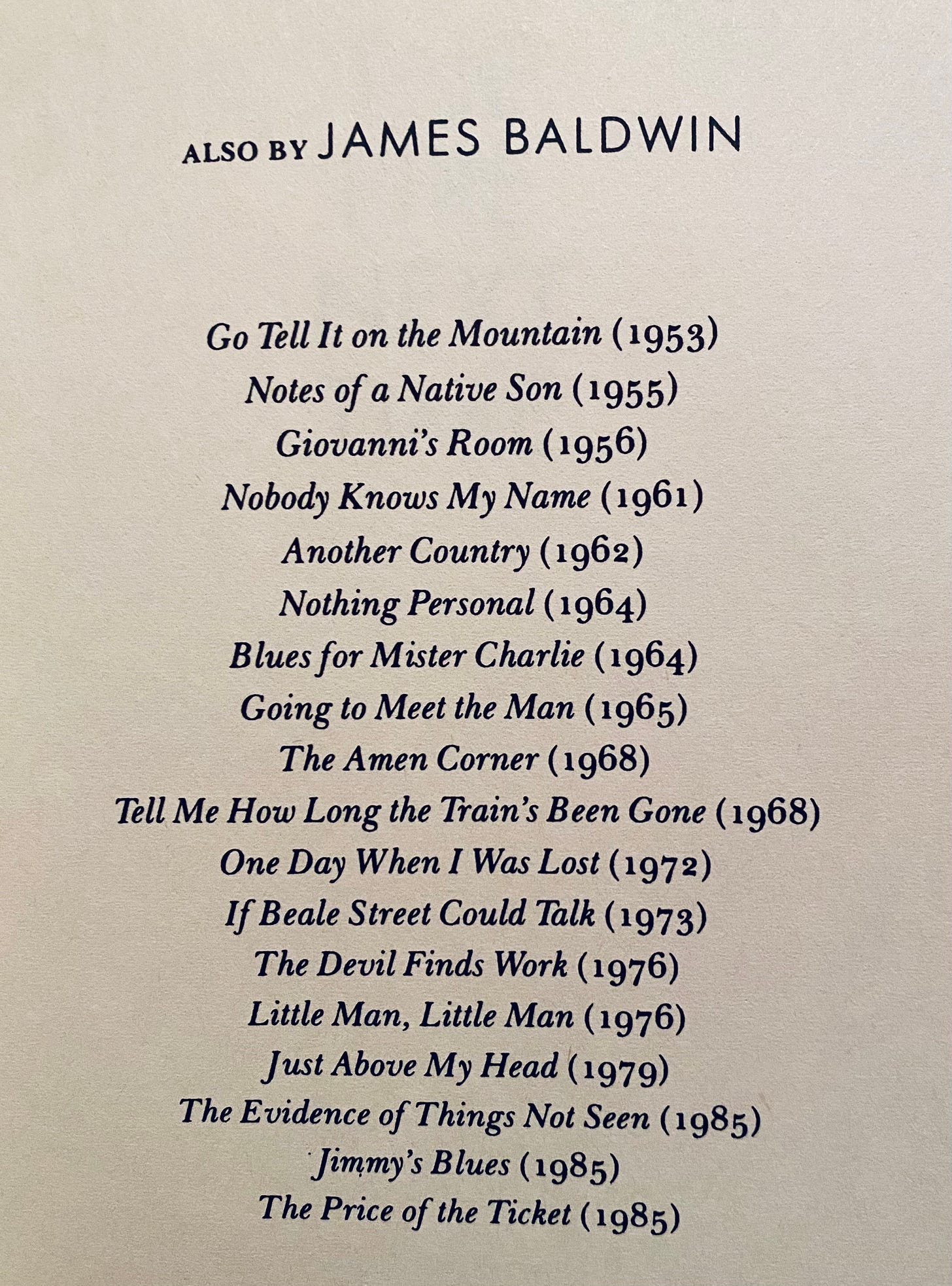

In 1953, James Baldwin published his debut novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. This semiautobiographical novel tells the story of 14-year-old John Grimes. Like Baldwin, Grimes was raised in New York City by his mother and stepfather, a preacher with whom he had a complicated relationship. Baldwin's novel considers Grimes's struggles with faith, sexuality, and salvation while attending the Pentecostal church his father helms.

Go Tell It on the Mountain is the first Baldwin book I read, and it remains my favorite. I reread it a few years ago with one of my book clubs, and I loved it even more the second time around. The novel opens like this:

Everyone had always said that John would be a preacher when he grew up, just like his father. It had been said so often that John, without ever thinking about it, had come to believe it himself. Not until the morning of his fourteenth birthday did he really begin to think about it, and by then it was already too late.

I love this setup: John, newly fourteen, exists in a world in which his identity has been decided for him. He has never second-guessed it or even really considered it at all. Yet this day, John’s birthday, something shifts. He’s still just a child but is on the precipice of something new, something adult. But despite the boy’s young age, Baldwin makes it known that his fate has been determined and it’s too late to push back. In just these three opening sentences of his first book, Baldwin sets up a classic coming-of-age story and goes on to deliver a stunning novel that examines identity and faith in ways that are still relevant, 72 years after the book’s publication.

In addition to writing fiction, Baldwin also penned short stories, plays, and essays. In his nonfiction book The Fire Next Time, he shares a letter written to his nephew, also named James, upon the 100th anniversary of emancipation. (Read the whole letter here.) What he wrote to James in 1963 is, sadly, still vital truth for today’s readers:

This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. Let me spell out precisely what I mean by that, for the heart of the matter is here, and the root of my dispute with my country. You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity.

Baldwin became so disillusioned with America that he relocated to France. One of his most famous novels, Giovanni’s Room, is set in Paris. That book ventures inside the head of David, a white American, as he reflects on his brief but heated relationship with Giovanni, an Italian immigrant, that occurred while David was engaged to a fellow American woman named Hella. When this book was published in 1956, you can imagine that it caused a stir. Dr. Dan Dixon notes, "The novel was critiqued both for its queerness, and for not, as was expected from Baldwin, focusing explicitly on the struggle of Black America.1"

Giovanni’s Room is another story about identity and the emotional journey of discovering who you are. David reflects on his move from New York to France, thinking:

Perhaps, as we say in America, I wanted to find myself. This is an interesting phrase, not current as far as I know in the language of any other people, which certainly does not mean what it says but betrays a nagging suspicion that something has been misplaced. I think now that if I had any intimation that the self I was going to find would turn out to be only the same self from which I had spent so much time in flight, I would have stayed at home.

I love this idea that who we are is who we are, no matter the location. We can’t outrun ourselves, and we can’t shrug off the important work of developing our sense of self. A new location isn’t always just about our personal identity, though. Sometimes it’s about seeing our homeland in a new light. In a 1961 interview with Studs Terkel2, Baldwin talks about his own time in France and how it shaped his view of America, saying:

I began to see this country for the first time. If I hadn't gone away, I would never have been able to see it; and if I was unable to see it, I would never have been able to forgive it. I'm not mad at this country anymore: I am very worried about it. I'm not worried about the Negroes in the country even, so much as I am about the country. The country doesn't know what it has done to Negroes. And the country has no notion whatever— and this is disastrous—of what it has done to itself. North and South have yet to assess the price they pay for keeping the Negro in his place; and, to my point of view, it shows in every single level of our lives, from the most public to the most private.

Baldwin was an outspoken activist for civil rights and would consistently engage in difficult and tense conversations about race and how Blacks were treated in the United States. He explored those struggles in 1974's If Beale Street Could Talk. This tender love story follows Tish and Fonny, two young lovers expecting a child together. Their bond is tested when Fonny is arrested and imprisoned for a crime he didn't commit. Baldwin writes, "It's a miracle to realize somebody loves you." Though Beale Street is about the difficult realities of racism, familial conflict, and unfair circumstances Black people face, Baldwin still infuses his writing with moments of beauty, celebrating the love between Tish and Fonny, and between Tish and her family.

His ability to write about the complexities and nuances of life with such a sharp prophetic voice is one of the reasons Baldwin's work has remained not only significant but beloved. I still have many more Baldwin books to read, and I’m grateful to know there’s still unread work out there, waiting for me.

Diving Deeper

If you’re interested in more Baldwin goodness, check out some of these resources:

VIDEO: Baldwin discusses racism on The Dick Cavett Show in 1969

VIDEO: Baldwin and Nikki Giovanni sit down in 1971 to talk about Black life in America and other topics

MUSIC: James Baldwin’s Home Records playlist

BIOGRAPHY/POEMS: James Baldwin from Poetry Foundation

ESSAY: Refinding James Baldwin from the New Yorker

INTERVIEW: Baldwin talks to The Paris Review in 1984

VIDEO: A look at James Baldwin's enduring influence on art and activism with PBS NewsHour

MOVIE: I Am Not Your Negro

https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2024/08/29/fear-queer-love-and-self-loathing-james-baldwins-masterpiece-giovannis-room.html#:~:text=When%20Giovanni's%20Room%20was%20finally,the%20struggle%20of%20Black%20America.

https://bookshop.org/a/101918/9781612194004

If you’d like to support my work, comment, share, upgrade to a paid subscription, buy me a coffee, or shop my bookshop or affiliate links. I love doing this work, and I’m thankful to have you in this community!

Are you a Baldwin fan? I’d love to hear your thoughts on his writing and legacy. Thank you for reading!

“I love this idea that who we are is who we are, no matter the location. We can’t outrun ourselves, and we can’t shrug off the important work of developing our sense of self.”

Love this and love that one of America’s great minds fooled himself for a minute into believing such a thing was possible. Great post!